Dying without an elephant

Toward the end of my brother’s life, he spent every waking hour in a faux-leather armchair by his living room window. He was companioned by the puff-puff-puffing of an oxygen concentrator, a walker with a basket full of pills, a laptop that helped him stay connected to people around the world—and an elephant.

I don’t know whether the elephant’s name was Denial or Hope, but the sicker my brother got, the bigger the elephant grew, nourished on secrecy, silence, and relentless positivity. The floor around its feet was covered in eggshells.

That elephant robbed me of some of the most meaningful time I could’ve spent with my brother. I never got to tell him how much I admired and loved him. I didn’t get to thank him or relive memories that only the two of us shared. And I never got to say goodbye.

I didn’t realize what I’d missed until Kelly Lindsay was diagnosed with glioblastoma and began writing about his experience in a CaringBridge blog. He refused to embrace battle metaphors. He wasn’t “fighting” cancer, his tumor wasn’t an “invader,” and he wasn’t striving to “beat” a disease that would eventually kill him. Instead, he strove to unconditionally love it.

Not only was Kelly’s experience elephant-free, his choice to love his tumor put me in an uncomfortable position. I could not love Kelly and hate what he loved. If I was going to love him, I had to love all of him, including his tumor.

I didn’t want to do that. I struggled to accept, much less love, the thing that was killing him. So, I asked Kelly for help.

“This tumor is part of me, and I’m actually grateful for that part,” he said from a faux-leather chair with a view out his living room window. “The whole year has been valuable. Not in ways I could really enumerate, and not in ways that, when I was first diagnosed, I’d say, ‘Oh, fantastic! That’s great news.’ As far as a learning experience, it’s not one I would’ve wished on myself or on anybody else, but it’s been pretty spectacular.”

Kelly had cancer once before, and his wife Diana had it twice. She was diagnosed with stage four lung cancer in 2006, and oncologists gave her three to 12 months to live. Kelly was her caregiver then and, miraculously, she became his caregiver more than a decade later.

The two of them were in cancer graduate school, and that might be what enabled Kelly to harvest riches from an experience that everyone else would rather avoid. He said the year after Diana’s diagnosis was the best one of his life.

“And this year, if it’s not the best year, is the second-best,” he said. “It just shows how wrong I can be about a big picture. It’s all actually pretty exciting, Petra. In a way I wouldn’t have thought.”

Kelly and Diana transmuted their cancer experience into something that has benefited hundreds, if not thousands, of people through the founding of a nonprofit called Healing Circles. It offers social support through small groups of people (called circles) who have a challenge or interest in common.

“In a lot of the circles at Healing Circles, people have focused on death and dying and made it an interesting, intriguing part of life,” said Kelly. “Instead of this scary, awful thing that ends something, it starts something, and you don’t want to miss it. I want to know when the side effects end so I can enjoy this other part of it that doesn’t need to be scary. It doesn’t even need to be endured. It needs to be enjoyed, so that’s probably where the loving part comes, too. This is a whole new aspect of life. Why rush through it?”

Loving someone who’s dying without an elephant is excruciating. It was difficult to simultaneously hold onto Kelly and let him go. To stay present with him and grieve the loss that I knew was coming. I say that as a distant planet orbiting Kelly’s sun. By contrast, the orbit of his brother Tom brought him much nearer, close enough to be overcome by his love for Kelly and the loss he knew was imminent.

Could I have born the anticipatory grief that Tom bore for Kelly? Could I have grieved for my brother the way Tom grieved for his? Would I have had the courage to speak openly about the death we both knew was coming?

I think so. I prefer the present pain of acceptance to the deferred pain of denial. Death comes with or without an elephant, and grief is inevitable.

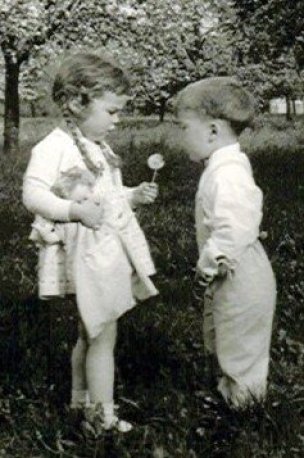

“Petey” and “Tommy”

When Tom’s friend Bin, whose mother died of glioblastoma, learned that Kelly had been transferred to hospice, he wrote, “Lean into this crazy shit, my friend. The only thing worse than what’s happening is pretending it’s not.”

I didn’t have the opportunity to lean in with my brother, and pretending that he wasn’t dying didn’t keep him alive. So, I will say now what I couldn’t say then.

Thank you, Tommy, for being such a good-natured companion throughout our child- and adulthood. I can’t remember a time when you didn’t take the high road.

Thank you for your thoughtful kindness and for the compassionate way you advocated and cared for our parents. And thank you for loving me in a way no one else could.

I miss your bear hugs. I miss your mind. I miss our in-jokes and the way you called me “Petey.” I even miss the noogies.

There are nearly eight billion people on this planet, but it feels empty without you.

Originally published at petramartin.com. Republished by permission.